I did a week-long film-making intensive course in November 2018 at AFTRS (Australian Film, Television and Radio School), where its alumni had won Academy Awards for films such as The Lord of the Rings, Memoirs of a Geisha and The Piano.

My motivations behind it is not to move to Hollywood, but to satisfy my curiosity as a product manager on what making a film product is like.

“A director makes 100 decisions an hour. If you don’t know how to make the right decisions, you’re not a director.” - George Lucas, creator of the Star Wars and Indiana Jones franchises.

As product managers, not only do we need to communicate externally a story on why customers need our products in their lives, but also communicate internally to align our colleagues around our vision.

The product manager is the product storyteller.

Similarly, the most important thing in a film is the story.

The crux to a good story is always asking yourself as the story-teller - How is your character and audience feeling? When I look at this in the context of product management, I imagine our audience as customers and company stakeholders, and the character as the product that we own.

How can we invoke the feelings that we want to invoke with each story told? How can we make our audience feel what our product feels?

What better way to learn about storytelling than from Pixar, one of the greatest storytellers of all time?

There are usually 4 common goals for a film’s story. Will your story be about:

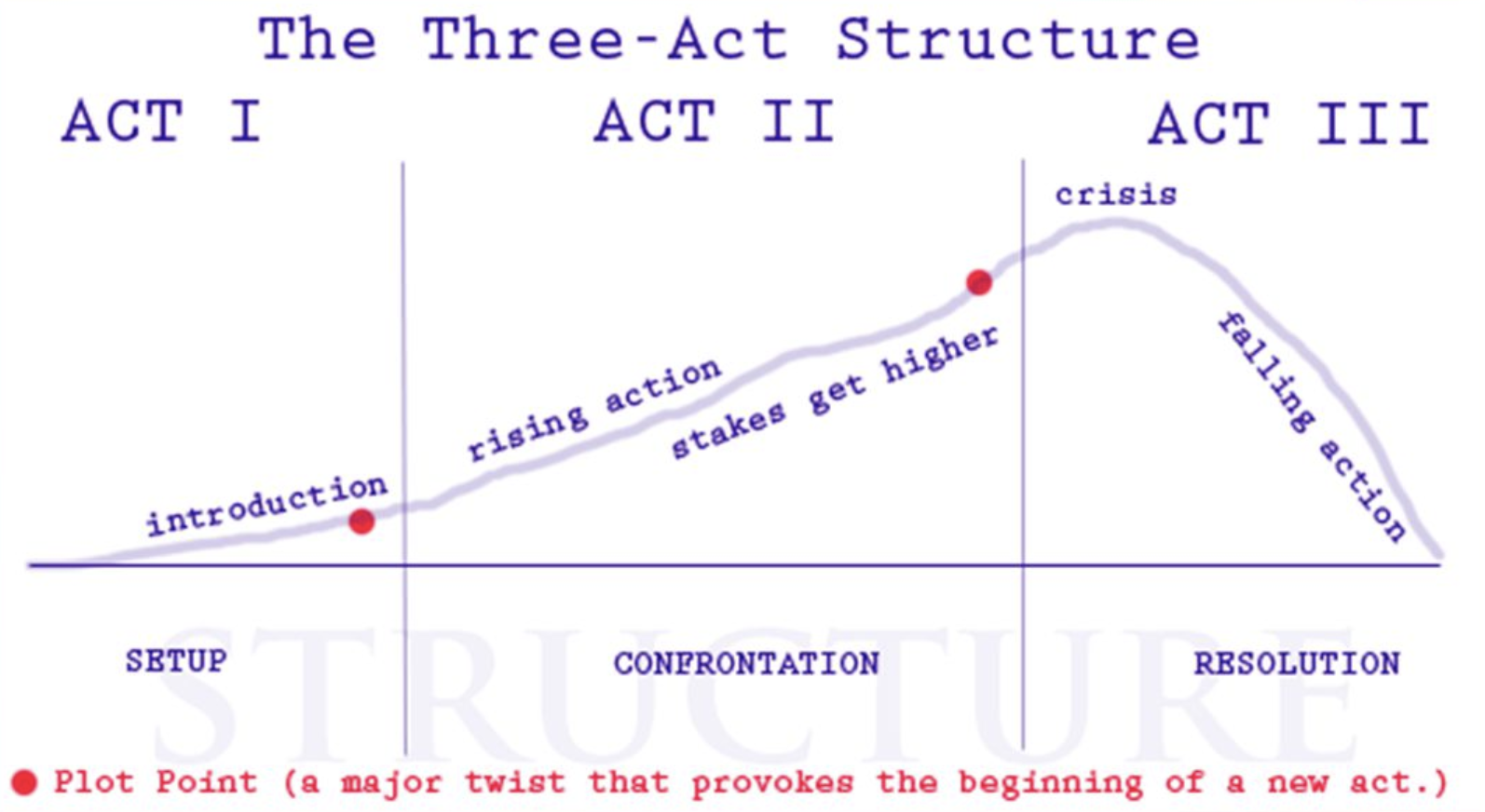

We were taught the 3 act structure mirroring the Hero’s Journey popularised by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 work The Hero with a Thousand Faces, where the:

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

If we look at our hero as our product, what would its Hero’s Journey be like?

Dan Harmon (creator of Rick and Morty and Community) has since simplified the theory into 8 steps:

A good story always contains conflicts, of which it can be broken down into:

An example is Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz.

An exercise that I enjoyed immensely was when our teacher flashed a series of images of people and told us to come up with a story within 5 minutes for the one that we found a strong connection with.

I was reminded of Google’s Crazy 8 design sprint, which we use to create an experience canvas at work.

I connected with the image of a granny, spinning up a story of ageing and loneliness, due to her husband’s death and her adult children being busy with their own families - when life started to take a turn for the worse when she started losing her memory.

If we can think about writing user stories as writing for characters in a film, will that make a difference in how much we understand our customers and make for more compelling user stories?

Research into personas has determined that it’s not solely our users' job titles or roles that guide the way they work. It’s more to do with their personality traits that shape their behaviour and attitudes.

Imagine Alana, who can easily be a QA manager, product manager or a senior developer.

Alana, “I'm about to make the call on this, so show me everything I need to know. The more I know end-to-end, the better my decisions are.”

Alana is great at motivating a team along when times get tough. She constantly drives for outcomes and feels that details get in the way when she’s busy, (which, if you’ve had a meeting with her, you’d realise is almost always). She abhors admin work or things that get in her way. In her workplace, she prefers direct communication from her colleagues and managers.

Alana is actively involved in professional circles outside of work and likes to keep up with the news by reading management and productivity books.

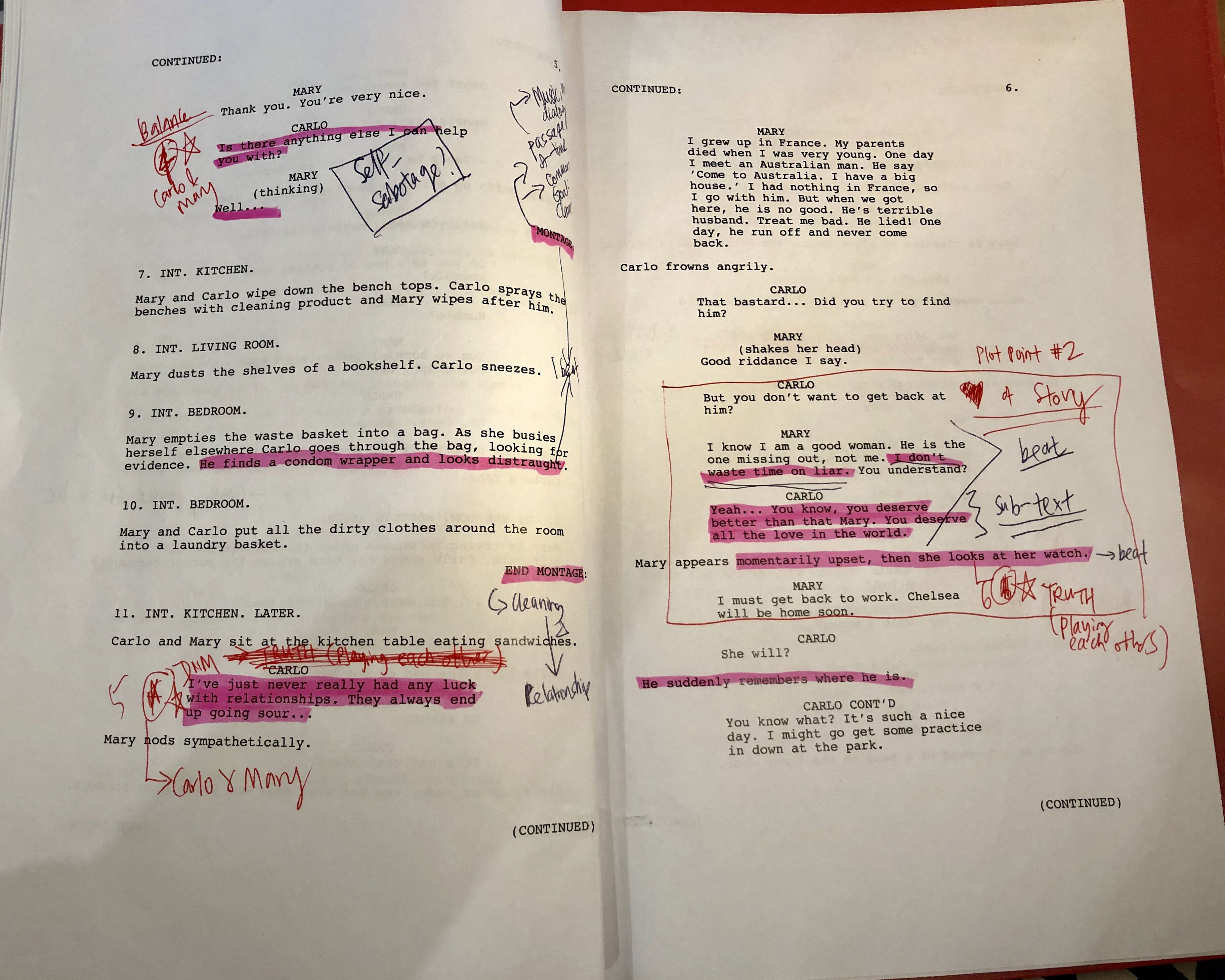

We analysed the script and were asked to identify the parts where we thought were important.

This is usually something where there is a change from the status quo - it could be a new character introduced, the meeting of hearts, a power dynamic change between characters or a climax/twist.

We call this a beat.

A short film like this (~10 minutes) will probably have a maximum of 5-6 beats, so we started with around 10+ beats and culled it to 6 core ones.

Of all the different beats, there will be the heart of the film in one of the beats. If we had to only show one scene, this will be the beat that we will show.

When we think about how we do our prioritisation, knowing what are the beats and the heart of our product can help us determine what is important.

Do you know what the heart of your product is?

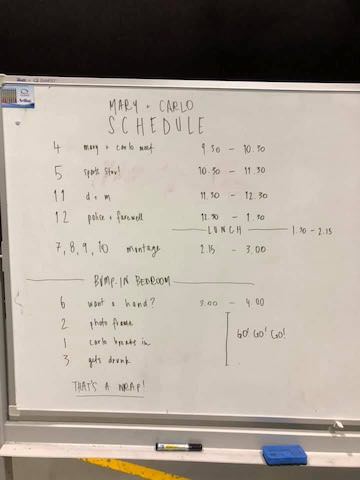

After spending a few days learning, setting up the set, and filming with the actor and actress, we went about working with the sound engineer and film-editing software to make the final cut!

Mary & Carlo - AFTRS Filmmaking Intensive Nov 2018

I really enjoyed learning about how the film-making industry works, and saw that there are many parallels to making a good software product.

If you are interested to chat about films, my favourite are thrillers and horror movies of different genres (e.g. psychological, paranormal, fantasy etc.)!

Leave me a message to comment about this blog post!

Is product management more of an art or a science?

Understand SaaS, PaaS, IaaS, CaaS and FaaS in Cloud Computing